Apologies for my language, but who really gives a shit about shit?

Following rapid population growth, the African Development Bank (AfDB) projects that Africa’s population will increase from 1 billion in 2010 to 1.6 billion in 2030. This rapid growth has outgrown the rate of infrastructural construction. This problem is made worse by the increased number of informal settlements, inadequate governance, poor urban planning, and limited access to water sources.

Due to this, approximately 900 million people worldwide are still forced to defecate in the open because they do not have access to a toilet. This is shocking given that sustainable development goal 6 focuses on sanitation and access to toilets. What about those who do have access? I hope that by now I have shown that simply having the physical infrastructure available is not enough! Access to toilets is not contingent on having the infrastructure, instead, this can be affected by maintenance, location, and opening hours.

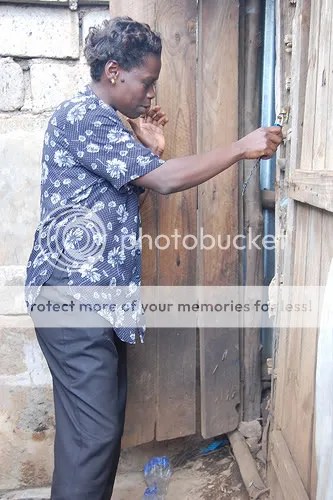

In many places, such as Nairobi, communal toilets are common as they provide a safer alternative to open defecation, but at the same time turn what we perceive as a private bodily practice into a shared affair. Jane Iyeango, a resident of Kibera slum (Nairobi, Kenya), manages their community toilet (image one). Jane is responsible for monitoring the use, hygiene, and opening hours as well as ensuring the toilet is locked at times of closure.

Locals, including Jane, pay a monthly fee to access the toilet. This immediately restricts certain users as they may not be able to afford it. In doing this, the toilet becomes a luxury good rather than an infrastructure that facilitates a basic need. Those who are lucky enough to afford to pay and use the toilet are not provided with running water. Along with this, it is closed during certain times of the day. What are people supposed to do if they need to use the toilet during the night? Therefore, simply having toilets in communities is not enough and certainly is not a solution to open defecation.

Girls and women have to choose

Women are disproportionately impacted by this as they often require more privacy, especially during menstruation. This makes them more vulnerable to abuse.

“I had heard that it was unsafe to visit the (community) toilet alone […] I reasoned that since it was only 7:30 p.m., and many people were walking around, it would be safe to visit the toilet, which was located only about 100 meters away. [..] The moment I unlocked the toilet’s wooden door to walk back home I was dragged to an abandoned house where I was abused, in turns, by five men until I blacked out.” (Rebecca Nduku)

Unfortunately, these stories are common and have become the new norm, with women without access to sanitation facilities being 40% more at risk of sexual assault than those with access. The solution is found in staying in large groups when needing to defecate or avoiding going out in the dark. This is absurd! Why should women feel at risk or unsafe when they want to go to the toilet? Why should they have to choose whether to go to the toilet and potentially be attacked, or refrain from such activities?

Across the African continent, 30% of Africans had access to a toilet and yet 93% had mobile phone service - more people have access to a mobile phone than a toilet! In terms of development, sanitation seems to be an afterthought, if considered at all. This issue needs to be addressed in the state and a top-down manner as toilets and sanitation are often camouflaged behind the aims and goals of access to clean water. Although the two are intertwined, they need to be addressed and considered separately as I think we are going through a shift in which this is happening – people voices are being heard and governments are being held accountable. However, this pressure must be maintained to ensure that action is taken. This will be discussed further in the following blog.

Following rapid population growth, the African Development Bank (AfDB) projects that Africa’s population will increase from 1 billion in 2010 to 1.6 billion in 2030. This rapid growth has outgrown the rate of infrastructural construction. This problem is made worse by the increased number of informal settlements, inadequate governance, poor urban planning, and limited access to water sources.

Due to this, approximately 900 million people worldwide are still forced to defecate in the open because they do not have access to a toilet. This is shocking given that sustainable development goal 6 focuses on sanitation and access to toilets. What about those who do have access? I hope that by now I have shown that simply having the physical infrastructure available is not enough! Access to toilets is not contingent on having the infrastructure, instead, this can be affected by maintenance, location, and opening hours.

In many places, such as Nairobi, communal toilets are common as they provide a safer alternative to open defecation, but at the same time turn what we perceive as a private bodily practice into a shared affair. Jane Iyeango, a resident of Kibera slum (Nairobi, Kenya), manages their community toilet (image one). Jane is responsible for monitoring the use, hygiene, and opening hours as well as ensuring the toilet is locked at times of closure.

Image one: Jane Iyeango unlocking and showing the community toilet. Source

Girls and women have to choose

Women are disproportionately impacted by this as they often require more privacy, especially during menstruation. This makes them more vulnerable to abuse.

“I had heard that it was unsafe to visit the (community) toilet alone […] I reasoned that since it was only 7:30 p.m., and many people were walking around, it would be safe to visit the toilet, which was located only about 100 meters away. [..] The moment I unlocked the toilet’s wooden door to walk back home I was dragged to an abandoned house where I was abused, in turns, by five men until I blacked out.” (Rebecca Nduku)

Unfortunately, these stories are common and have become the new norm, with women without access to sanitation facilities being 40% more at risk of sexual assault than those with access. The solution is found in staying in large groups when needing to defecate or avoiding going out in the dark. This is absurd! Why should women feel at risk or unsafe when they want to go to the toilet? Why should they have to choose whether to go to the toilet and potentially be attacked, or refrain from such activities?

Across the African continent, 30% of Africans had access to a toilet and yet 93% had mobile phone service - more people have access to a mobile phone than a toilet! In terms of development, sanitation seems to be an afterthought, if considered at all. This issue needs to be addressed in the state and a top-down manner as toilets and sanitation are often camouflaged behind the aims and goals of access to clean water. Although the two are intertwined, they need to be addressed and considered separately as I think we are going through a shift in which this is happening – people voices are being heard and governments are being held accountable. However, this pressure must be maintained to ensure that action is taken. This will be discussed further in the following blog.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteHi Anda, I love how this post highlights the devastating realities of women and their experiences of the toilet. This leads me to ask what initiative do you think needs to be undertaken in order to help African countries like Kenya tackle gender-based violence? Would that be a more bottom-up approach?

ReplyDeleteHi Donita, thank you for reading this post and for your question. I think that although bottom-up approaches allow for greater participation and inclusion, I think top-down approaches are needed to address gender-based violence. A priority should be to increase street lighting and patrols to improve safety. Past this, NGOs play a vital role in introducing new initiatives and programmes to end gender-based violence and meet SDG 5.2 (e.g. https://thecircle.ngo/project/gender-based-violence/).

DeleteHi Anda. Fantastic post. I completely agree with you, why should women have to take 'precautions', such as going in groups, to be able to go to the toilet safely? This is such an unfortunate reality for women of all ages across Africa, both in rural and urban environments. Sanitation, for so long, has been an overlooked issue in policy and development debate, and since the realities are so devastating, we can only hope that in coming years, this issue will be properly addressed. Looking forward to reading your next post.

ReplyDeleteHi Greta, thank you for your comment! This is definitely a challenging topic to discuss espcially from the position of a female as the norms in one place, particularly in the Global South, are unthinkable or even absurd to me who doesn't really have to think twice about finding access to a toilet. This is something I explore further in my next blog where I discuss taboos and start to consider the impacts of not talking about these issues.

Delete